(The slope that led to life was never level)

A meditation on chirality, light, and the origins of molecular choice

There was a moment, before biology, before folding, before the wet chemistry of life had even organized into whispering codes—when light, moving across an ancient galactic span, tipped the scale. Circularly polarized light from a distant star may have favored one handedness over the other. A gentle, photonic skew. In the cold dark, it destroyed just a few more D-amino acids than L. This bias, subtle as breath, etched its whisper into meteoritic stone. When those stones struck Earth—like the amino acid-rich Murchison meteorite—they carried with them that primordial leaning. Left-handed amino acids, in slight excess. A prebiotic seed, already asymmetric. And life, when it emerged, grew from that tilt. From the stars to the soil. From photons to proteins. That is the inheritance of bias.

Billions of years later, perhaps on an otherwise unremarkable Saturday afternoon in 1848, a 25-year-old scientist sat quietly in his lab in Strasbourg, peering into a lens. Louis Pasteur, not yet legendary, held a pair of tweezers and a question. He was studying crystals of sodium ammonium tartrate—tiny, glittering structures formed from wine residue. What he noticed was not expected: the crystals came in two distinct shapes—mirror images of one another. Left-handed, right-handed. He separated them by hand, one by one, with almost monastic patience. When dissolved, one form rotated polarized light clockwise; the other, counterclockwise. A perfect symmetry hidden in plain sight. Mixed, they cancelled. Separated, they revealed. It was a quiet experiment with thunderous consequence. Pasteur had discovered molecular chirality—handedness at the atomic scale. It was the first time anyone had shown that mirror-image molecules could behave differently. And though he could not yet know its full importance, he had stepped into a lineage that began long before the Earth cooled. His paper, titled “Sur les relations qui peuvent exister entre la forme cristalline, la composition chimique et le sens de la polarisation rotatoire,” did more than describe a phenomenon. It marked the beginning of stereochemistry, of biochemistry’s structural alphabet. It offered a glimpse into the spatial language of life.

Chirality is not merely a quirk of geometry—it is a principle that shapes existence. Proteins fold in one direction because the ribosome only recognizes L-amino acids. Enzymes catalyze with handed precision. Membranes, receptors, neurotransmitters—all lean into this asymmetry. From helix to thought, the slope continues. Consciousness itself—rooted in the chiral molecules that make neurons fire and memories form—emerges from a foundation already slanted.

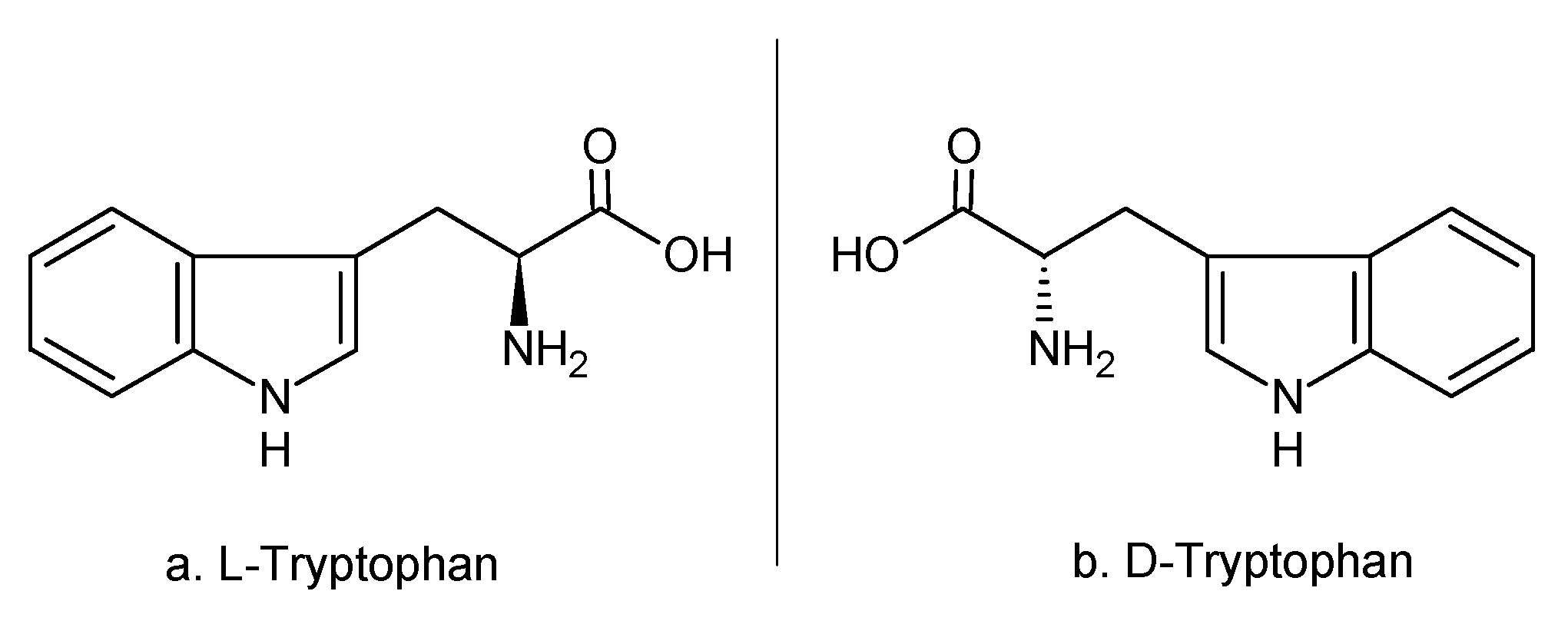

Tryptophan—coded by the single letter W—is just one of twenty amino acids that scaffold life. It folds into serotonin and melatonin, into memory, sleep, and the architecture of mood. In its D-form, it lingers unused, uninvited by the ribosome—a mirror image excluded by ancestral preference. This is not neutrality; it’s inheritance. A molecular echo of a choice made before choices. And somewhere in that alphabet of life, I find myself reflected. W, both molecule and moniker—a quiet convergence. Just a letter. Just an acid. Just a fold I happen to share.

But that is the nature of this field. We reflect ourselves through what we study. Our hypotheses carry more than logic—they carry memory, instinct, preference. A scientist may choose a model; a builder, a material; a painter, vermilion over blue. None of it is neutral. Those who create—whether with pigment, wood, equations, or time—infuse the world with bias through intention. And once intention is introduced, the symmetry is broken. Not ruined—revealed. Meaning emerges not from the center, but from the tilt. This is what Pasteur did, whether he knew it or not. He didn’t invent the asymmetry—he noticed it. He bent close to the crystals and allowed the world to show its slant. And so the universe shifted. A small choice. A hand separating forms. An afternoon spent noticing. That is the seed of influence.

We carry that same power. Every choice, every frame, every question—each one tilts the fractal. And the universe, responsive and recursive, holds that shape. It resonates forward. I return to this lineage now. I sit, like Pasteur, on a quiet afternoon. The light here in Stockholm slants low across a table. Dust floats between beams. I imagine him: young, exacting, unaware of the full weight of what he was uncovering. I wonder how often we hold something transformative without knowing. How often we are the lens, or the light, or the residue. How often a choice—or a molecule—echoes across generations.

Perhaps this is what it means to be part of a causal fractal. To be a node in a self-amplifying pattern that stretches from meteors to microscopes to molecular drug design. I am not outside this system; I am composed of its curves. My thoughts arise from its angles. Even the questions I ask—about amyloid, about protein surfaces and cryptic grooves—are shaped by the chirality that once bent a photon, long before my ancestors drew breath. That is the resonance: that we are not observers of asymmetry, but participants in it.

As I work toward mapping the unknown folds of proteins, trying to predict and disrupt the pathological curves of amyloid, I carry Pasteur’s tweezers in metaphor. I sort structures. I look for bias—not to eliminate it, but to understand it, perhaps even to wield it. What if we could bias the presence of certain protein conformations, not just react to them? What if the asymmetries that gave rise to life could be guided forward, shaped with intention? This is no longer just science. It is story. It is philosophy written in carbon and light. It is art made from the inside out.

To know that the foundations of life were tilted—not by will, but by happenstance—is to realize that our very presence is a continuation of that leaning. We are the outcome of a molecular preference, and we become, in turn, the source of new ones. Through our discoveries, through our questions, we tilt the world in return. We are light, bending. And in that bending, we become the seed of future bias. We create structures that will shape what follows. Some will be proteins. Some will be art. Some will be systems. Some will be stories. All will fold from the asymmetries we leave behind.

So I ask myself now—not what symmetry I preserve, but what asymmetry I amplify. Not what balance I uphold, but what bias I leave in my wake. Because life does not emerge from the midpoint. It emerges from the break. The wine residue of 1848. The Murchison meteorite. The quiet afternoons where questions become discoveries. This is the long arc of chirality—of molecular directionality turned into meaning.

And knowing this, I ask again: what small asymmetry will shape what comes next?