The First Direction

Rex Gaskins didn’t push me into science. He opened a door and left it wide. I walked through because I had to—because after growing up in a family trucking company, where I spent my high school years around diesel engines and steel-hauling convoys, I saw machines everywhere. Pistons, pressure, movement. Systems made sense. And when I learned about proteins, something clicked: these were molecular machines. Coils and switches and gears built of atoms, folding and unfolding into function. Biology wasn’t just alive. It was engineered.

So when Rex suggested I look into polarity, not in people but in single cells, it didn’t feel like a leap. It felt like tuning a carburetor with a pipette. He said, in essence, “Go find where direction begins.” And I did.

I began with cows and sheep, with surgical windows into their rumens. There, swimming through a hot, fermenting ocean of digested grass and symbiotic bacteria, I met Entodinium caudatum and other rumen ciliates. These creatures were mind-bending. No extracellular matrix, no neighbors, no orientation cues—and yet they were polarized. Mouth on one end. Tail on the other. They spun and fed and divided with purpose. They were machines too, just built from membrane and microtubules, sensing their world with gradients of sugar, pH, and chemical whisper.

They didn’t just swim—they danced. They brushed against each other, paused, recoiled or circled back. Touch as question. Movement as language. Friend or foe? Food or obstacle? Their decisions were written in waveform, in ion currents, in the soft binary of attraction and repulsion. Their membranes read the world, and their cytoskeletons replied. It was social, in a way. Tender.

Their sensors were proteins. GPCRs. Ion channels. Voltage differentials. They navigated not with thought, but with signal. Their membranes were aware. They read the environment and wrote behavior in response. No neurons, no synapses—just the language of charge and shape.

To understand them better, I reached out to David Nanny, a quietly brilliant professor of cell biology at the University of Illinois. David had spent his life with these organisms. He gave me cultures of Tetrahymena thermophila and a way to watch them closely. Where the rumen was wild, his cultures were calm. But the intelligence was still there—the choreography of cilia, the sense of purpose without cognition. I visited his lab often. He didn't overwhelm with detail; he showed me how to see. David passed away years later, but his science still moves through me like signal through a membrane.

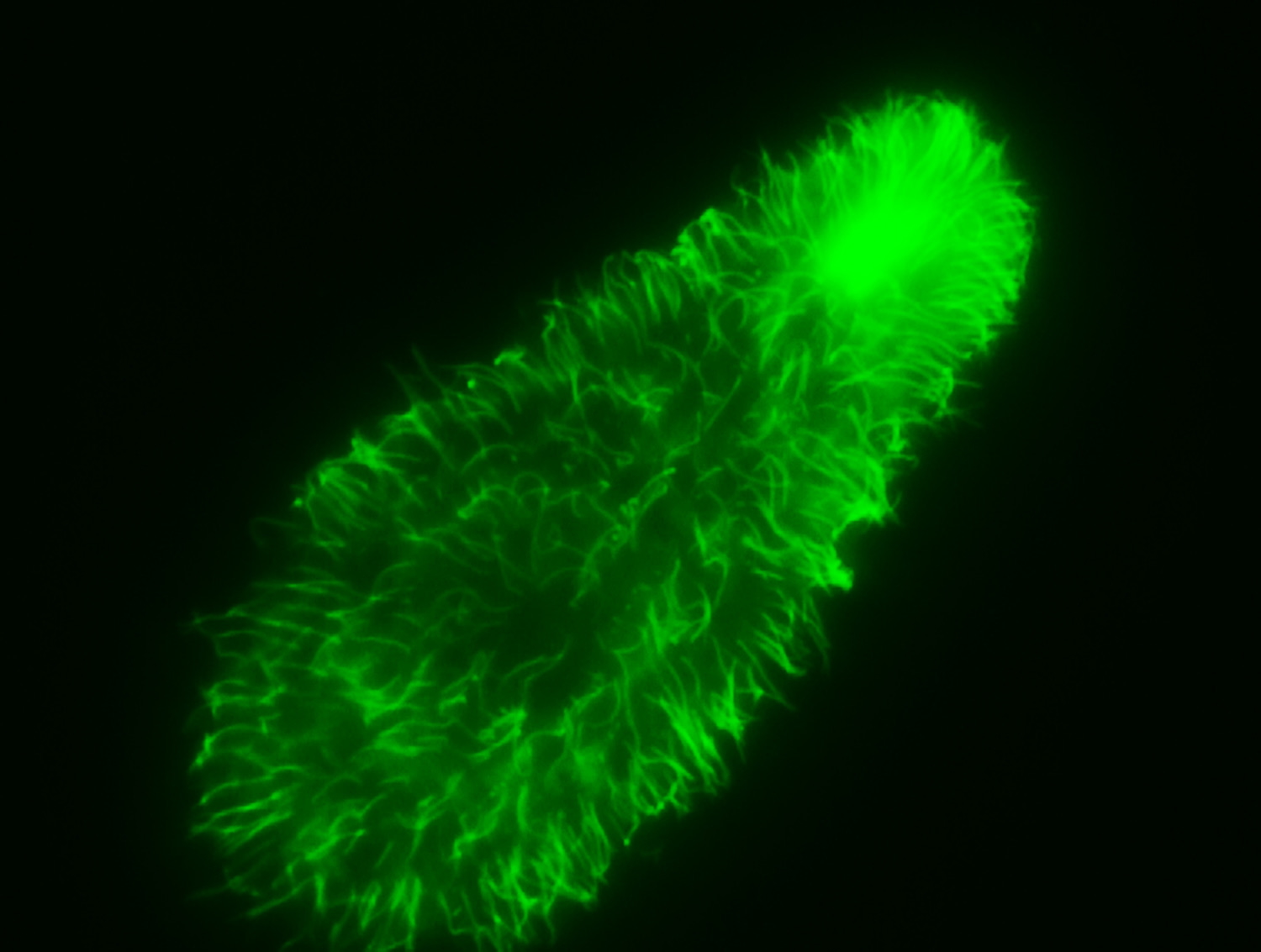

I often think back to that month in 1999, when I crossed the Atlantic to work in the lab of Dr. Bernard Vigues at the University Blaise Pascal in Clermont-Ferrand, France. I was young, uncertain, and barely fluent, but I was welcomed into a world of glass slides and electron beams. Bernard taught me how to prepare samples for TEM, how to run western blots, and most importantly, how to slow down and look. I stained Tetrahymena actin with a fluorescent dye, and under the scope, they glowed like green ghosts—the cytoskeleton blooming into view. I didn’t know it then, but I was seeing the language of folding.

Clermont-Ferrand itself was folded too—nestled in the Massif Central, ringed by dormant volcanoes and medieval rooftops. The air was clean, sharp, humming with the memory of geologic force. I would walk to the lab each morning past sun-warmed stone, through alleyways that smelled of espresso and lichen. And in that quiet rhythm, the actin filaments I saw under the microscope didn’t feel so distant from the basalt ridgelines above.

The upper right is the mouth. The body trails down to the lower left. Each cilium not just for motion, but for knowing. They were alone, but not solitary—a part of a quiet, shimmering community of sensation. Looking at them was like looking at an idea caught mid-gesture.

Back in the Clermont lab, I purified their proteins and ran SDS-PAGE gels. I watched identity resolve into bands. The invisible became visible. I felt the shape of understanding emerging like a structure out of solution.

Now, in my current work, I study Alzheimer’s disease—where polarity is lost. Where microtubules disintegrate. Where the machinery of memory falters. Amyloid plaques. Tau tangles. Signal turned to noise. And I think of Tetrahymena, still, with their graceful precision and their clarity of motion. Their folded surfaces know where they are going.

Life, I think, is shaped by gradients. We fold ourselves toward sensation, toward signal, toward one another. We are membranes, unfolding into time, responding to things we cannot see but deeply feel. Ciliates do it with molecules. We do it with memory. With yearning. With the act of building something beautiful from what was previously undifferentiated.

Ciliates don’t worry about their inboxes. They don’t wonder if they’ve disappointed anyone. They don’t carry the weight of memory, or hold futures that might never arrive. They move through their world one molecule at a time—navigating gradients, sensing sugar, responding to light. Entire lives unfold in the flicker of their cilia. They are complete within themselves, singular and sufficient, adapting not through overthinking, but through presence. And yet, in that simplicity, there’s a mirror. Because we, too, are sensing beings—multicellular mosaics of longing and signal. We chase gradients of meaning the way they chase glucose, drawn by echoes of love, by warmth that reminds us of home, by voices that once called us in from the dark. The ciliate folds toward sustenance. We fold toward each other. We seek recognition, connection, family. We ache across time for something we can feel but not name. Maybe every act of kindness, of building, of grief, is our way of responding to the invisible gradients around us. Not simpler, but not so different either. Maybe, in all our folds and feedback loops, in our memories and mistakes, we are still just trying to find the signal that leads us home.

I haven’t divided. Not yet. But maybe this writing is replication. Maybe this science is a form of folding. Maybe legacy is a gradient we swim toward, never fully arriving, always sensing.

Because even now, I believe: we are not so different from Tetrahymena. We, too, are swimming toward sugar, toward signal, toward light. Searching for the next molecule that might make us whole again.